Christian Felber

Initiator of the Economy for the Common Good

Christian Felber is founder of the The Economy For The Common Good based in Austria, a movement uniting over 10,000 supporters in 40 nations and backed by 2,000 companies whose mission is to eliminate the fundamental contradiction between business’ values and social well-being. He is the author of 15 books, including, most recently, Change Everything: Creating an Economy For The Common Good (Zed Books-UK, 2015; distributed in the U.S. by the University of Chicago Press). His book Money: The New Rules of The Game was awarded the 2014 getAbstract International Book Award. An internationally renowned speaker, Felber has given TEDx talks in Brussels and Vienna, and has addressed the European Economic and Social Committee as well as the U.K.’s Royal Society For the Arts. He has been featured on Triple Pundit, Alternet and CNBC.com. Felber is an adjunct lecturer at the Vienna University of Economics and Business and is also a modern dancer.

January 15, 2018

Review on Claus Dierksmeier's: Reframing Economic Ethics. The Philosophical Foundations of Humanistic Management.

Review of Claus Dierksmeier's: Reframing Economic Ethics. The Philosophical Foundations of Humanistic Management.

Review on Claus Dierksmeier's: Reframing Economic Ethics. The Philosophical Foundations of Humanistic Management.

Christian Felber

By

Christian Felber, Contributor

Initiator of the Economy for the Common Good

Jan 12, 2018, 07:33 AM EST

|Updated Jan 15, 2018

This post was published on the now-closed HuffPost Contributor platform. Contributors control their own work and posted freely to our site. If you need to flag this entry as abusive, send us an email.

LEAVE A COMMENT

Enlightening Fundament for Economic Ethic

Claus Dierksmeier undertakes a long-term investigative journey through history in economic ethics. Surprisingly, he finds strong continuity from Aristotle via Thomas Aquinas to Adam Smith that economic activities in special and the economy as a whole were considered as means to serve an overarching goal such as the common good. Put in other words, ethics have always been the very foundation and source of legitimation for the economy and should, thus, be the fundament of economic and management theory, teaching and practice – different from today, where ethics is, at best, an add-on to „chrematistic“ economic and management studies or, at worst, considered as hindering to wealth creation and welfare achievement.

Dierksmeier calls for a readjustment in the relation of economics and ethics arguing that the three revisited giants – Aristotle, Thoma Aquinas and also, against wide-spread myth, Adam Smith (the “most-quoted and least-read economic thinker of all times”), would consider the separation of ethics from economics simply as „perverse“. Only after Smith, who was a professor of moral philosophy, the emerging economic science turned into the zombi discipline which it is still today in its mainstream: a positivistic, pseudo-objective would be-natural science with a broad hidden normative agenda that ranges from the caricature of the „homo oeconomicus“, the equalisation of rational choice with search for individual benefit and of individual benefit with financial gain on to the religious belief in endless and necessary GDP growth. All these implicit normative assumptions exert a strong influence not only on the mindsets of students of economics and current and future generations of managers and business leaders, but also on the decisions of policy-makers from the local to the global. In sum, they have an enormous impact on human liberty.

Advertisement

Contrary to the strategic (framing by) naming of “free markets”, “free trade” or “free enterprise”, this “one size fits all maximization paradigm” and its concomitant policies – from Washington Consensus over free trade agreements without linkage to human rights or planetary boundaries to unlimited inequality – is not only blatantly normative (against its self-misunderstanding and self-presentation as „value-free”), but it also limits the liberty of the many and can, thus, be considered as illiberal.

Dierksmeier, Claus (2016), published by Palgrave Macmillan, Springer Nature.

Dierksmeier, Claus (2016), published by Palgrave Macmillan, Springer Nature.

A special asset of the book is the further development of freedom theory overcoming the obsolete distinction between negative and positive freedom. Dierksmeier, who interprets and uses Immanuel Kant as a bridge-builder between the – equally valid – teleological and liberal paradigms, suggests a more useful distinction between quantiative and qualitative freedom. Whereas a quantitative idea of freedom regards freedom as a license or an asset (the more the better), qualitative freedom considers freedom a task (the better the more) linking it closely to virtue and ethics. The circle closes. En passant, Dierskmeier heals the unnecessary contradiction between freedom (falsely understood as independence from others) and responsibility (falsely understood as a burden) defining liberty as a human trait that flows out of virtuous and ethical attitude and that constitutes, together with the latter, our humanity: “Individual liberty and cosmopolitan responsibility, rightly understood, presuppose one another.”

Advertisement

Ring

Protection at every corner

Sponsored By

Ring

1,952

$359.00

Add to cart

Together with others, Dierksmeier develops a “humanistic management theory” in an international network. Together with other forces, such as the international initiative for pluralism in economics, these new insights are both solid and powerful enough to overcome the obsolete current mainstream paradigm of economics. I consider this slim but powerful book a must-read oeuvre for scholars of economic and business ethics, but it is equally enlightening for anyone searching for an economy that works for free and dignified humans and society as a whole on a healthy Planet.

Related

January 2, 2018

A Framework for Ethical International Trade

A Framework for Ethical International Trade

Trade policy must abide by the fundamental values guiding society from human dignity to sustainable development to the common good. We therefore call for an ethical trade policy.

Christian Felber

By

Christian Felber, Contributor

Initiator of the Economy for the Common Good

Jan 1, 2017, 02:36 PM EST

|Updated Jan 2, 2018

This post was published on the now-closed HuffPost Contributor platform. Contributors control their own work and posted freely to our site. If you need to flag this entry as abusive, send us an email.

"Free trade" vs. "protecionism"?

Trade is not a goal in and of itself. The term free trade is subsequently a misnomer. Equally, protection is not a goal in and of itself. That is why "protectionism" is also a misnomer. Trade is valuable and protection makes sense, but none of them should be taken to the extreme. It would be blind and destructive to carry international division of labor to its logical end: Everything that is produced anywhere is exported and everything that is consumed, is imported from somewhere else. Export ratios would be 100%. Likewise, it would be blind and harmful to close down borders and stop trade completely.

In the public debate, nobody is calling for either of these extremes. Nevertheless, the terms "free trade" and "protectionism" refer to exactly these extremes. A reasonable trade policy regards trade as a means and enhances it where it helps to achieve the diverse goals of economic, social and ecological policy. It also limits and regulates trade when it conflicts with these diverse and legitimate policy goals, which should be protected.

Trade is a tool, a means, which can be utilized in a destructive or in a constructive fashion. Depending on how trade policy is implemented, either the positive or negative effects will come to fruition. Trade in slaves, children, organs or poisonous waste is forbidden and few would argue to the contrary. Trade policy must abide by the fundamental values guiding society from human dignity to sustainable development to the common good. We therefore call for an ethical trade policy.

7 Cornerstones for Ethical International Trade

1. An international trade regime that turns all participants into winners and that serves the "universal good of the whole" (David Ricardo-footnote 1-) can be regarded a global public good.

Advertisement

Its rules have to be democratic, transparent, fair, and sustainable. The best place for such a public good to be anchored is the United Nations Organization. The UNO is the core of the international law and it provides all necessary frameworks for an efficient and just trade regime: human rights, labour norms, environmental agreements, climate protection, sustainable development goals. The WTO treaties that were concluded outside the UNO to avoid these existing global standards and policies, should fade out in the same way as bilateral and regional treaties with an trade-is-an-end-in-itself approach. Particularly the US and the EU should not aim at an agreement outside the UN system (TTIP, TTP), but should work to strengthen it, and serve as role models in this endeavour.

2. Trade should serve universal goals and values, starting with human rights

The goals for which trade is a means are: the full implementation of all human rights, Sustainable Development Goals, Rights of Nature, cultural diversity, as well as frequent constitutional values such as justice, solidarity and human dignity. Those countries that ratify and comply with UN conventions and agreements - on human rights, labour norms, tax cooperation, environmental and climate protection, cultural diversity, and others - and who agree on a „UN Ethical Trade Agreement" (with at least 30 countries initially) should protect their higher commitments and standards both against non-ratifiers and non-compliers. They could, for example, place a 20% custom on imports from countries that have not ratified a particular human rights agreement, a 10% tariff for countries that have not ratified climate agreements and 3% for each core labor standard set by the International Labor Organization (ILO). This ethical tariff system creates an incentive to ratify and comply with the existing UN agreements. The consequence would be a „level playing field" concerning human rights, labor norms, social security and environmental protection and sufficiently high walls o protection against dumpers, freeriders and true "opponents of globalization". Finally, "soft" UN regulations in the area of human rights, worker's rights and climate justice will become "hard" international law.

3. Non-reciprocity between unequal trade partners

Historically, all industrial countries have used protectionist measures. This has served them very well. Protectionism made economic development possible in the first place. According to historian Paul Bairoch, the US is the "mother country and bastion of protectionism". Up until 1945, the US imposed duties on imports of up to 45% -footnote 2-. The USA learned this lesson from England, which could be considered the "grandmother of protectionism". Today, wealthy countries, in the WTO and in bilateral and regional trade agreements, are calling for "free trade" between countries with a lower degree of industrial and technological development. This is obviously unfair. Poorer countries should be able to sufficiently protect their markets until they have "caught up" to the industrialized countries. They should be able to use the same "ladder" to get over the wall of development that the industrial countries (including the seven Asian tigers) previously took advantage of -footnote 3-. This rationale for trade protectionism is referred to as the "infant industry argument" - an idea born in the USA.

Advertisement

4. Democratic freedom and "dancer's dress" instead of a "straightjacket" and "one size fits all" dogma

Development strategies framed around self-determination and individual design are important and often more efficient than one-size-fits-all strategies. In his book "The Lexus and the Olive Tree", Thomas Friedman introduced the term "golden straightjacket" for the current predominant economic policy scheme that includes a long series of restrictions and prohibitions to domestic policy makers, including the prohibition to use protective measures or to regulate investment -footnote 4-. We propose a "dancer's dress" to replace the straightjacket. This concept would include that: trade partners cannot take legal actions against democratically-legitimized regulations, neither on the basis of WTO or bilateral treaties; that investors cannot challenge "indirect expropriation" nor "unfair treatment"; or that sovereign countries are not limited in regulating investment according to their needs and political priorities. One recent example: Legal action has been taken in the WTO against European Union subsidies for Airbus and US subsidies for Boeing. These subsidies make sense for both sides and should not be subject to lawsuits as a result of "free" trade agreements. As for a principle, no country should be forced to open its markets more than it wants to and in ways that could be detrimental to its own economic policy goals. Dani Rodrik coined the slogan: "We need smart globalization, not maximum globalization -footnote 5-."

5. Localization, "economic subsidiarity", resilience, and cultural diversity

It is preferable that countries are economically independent in as many industries as possible and import specialized goods and services primarily through the global market. Division of labour and the use of comparative advantage - distributing the production of certain goods between different countries aiming for efficiency gains - is a possible option for specific cases, but is not a goal in and of itself. Globalization should be the salt in the local economic soup, instead of being the other way around (when trade is an end in itself = free trade). Whoever bakes their bread themselves and also grows the grain themselves is independent of fluctuations and crises on the global market. This applies to virtually all industries. Division of labour should be the well-reasoned exception, not the efficiency- and profit-driven rule. Economic dependencies should be kept to a minimum. John Maynard Keynes once wrote, "I sympathize, therefore, with those who would minimize, rather than with those who would maximize, economic entanglement among nations. Ideas, knowledge, science, hospitality, travel - these are the things which should of their nature be international. But let goods be homespun whenever it is reasonably and conveniently possible, and, above all, let finance be primarily national" -footnote 6-.

Advertisement

Samsung Galaxy Z Flip6 AI Smartphone, 12GB RAM, 256GB Storage, Blue

Sponsored By

Samsung

$1,789.00

Add to cart

6. Commitment to even trade balances

Principles 4 and 5 could invite countries to implement mercantilistic strategies: to limit importations or promote exportations at the cost of others, creating trade imbalances and global injustice. Lord Keynes, recognizing that trade imbalances lead to global instability and even wars, provided a clear tool for an international trade equilibrium, which could be properly implemented within the UN. The so-called "Clearing Union", which he proposed, would calculate all internationally traded goods and services in a new currency, called "Bancor" (today, we could call it "Globo" or "Terra"). This global reserve or trade currency would not replace, but complement national currencies for the international economic exchange. The goal of this new trade and currency union would be to ensure that all participating countries have equal trade balances. Keynes proposed that both countries with a trade deficit and a surplus would either re/devalue their currency or pay a fine according to the deviation. Keynes wrote: "We need a system possessed of an international stabilising mechanism, by which pressure is exercised on any country whose balance of payments with the rest of the world is departing from equilibrium in either direction, so as to prevent movements which must create for its neighbours an equal but opposite want of balance" -footnote 7-. This would bring an end to trade deficits in some countries and trade surpluses in others. An agreement on even trade balances would be the core of a fair global trade agreement. If this goal prevails, protective measures cannot be realized at the cost of others. Again, every country is free to be as open/closed as it wishes, it just cannot enhance exportations or limit importations at the cost of others. Keynes tool turns global trade competition into economic cooperation.

7. Limiting the power and size of transnational corporations

Transnational corporations have become too large and too powerful today and present a danger to freedom and democracy. This has not always been so in history. As late as 1800, only 200 corporations in the U.S. had received a license to operate by their corresponding state. In the 19th century, step by step, limited liability was introduced, the prohibition to own property in other corporations was suspended and, finally, in 1886, corporations became natural persons by the US constitution. Only after this progressive legal empowerment of corporations did they become as powerful as they are today. This was a mistake. Corporations should, therefore, be required to live up to their responsibilities towards society by:

a)growing only to a certain size (e. g. maximum turnover / total assets of 50 billion USD);

b)obtaining only a certain percentage of the world market (e. g. 0,5%);

c)democratizing internal structures when they become larger (progressive atomization of property and voting rights);

d)be required to complete a Common Good Balance Sheet. The result of this ethical balance sheet will provide companies with legal incentives by reducing their taxes, customs and by helping them in the areas of public procurement, grants and loan conditions.

Companies that fail to meet these standards would lose access to the "ethical trade zone" within the United Nations. They would only be able to operate in countries without limits on the size of corporations, on market shares and on concentration of power. Once these standards become commonplace, the concentration of power and the proliferation of corruption will decrease. Furthermore, the common good balance sheet will invert the current race to the bottom on global markets into a race to the top. The better its result, the freer companies can trade and invest or get market access. The poorer the result, the higher the difficulties they encounter - from tariffs to denial of market access. The „license to trade" depends on a company's contribution to the common good. As a consequence, ethical companies will win over less ethical ones, creating an ethical market economy - an economy for the common good.

Written with the collaboration of Gus Hagelberg: born in 1966, received his B.S. in Political Science from the California State University, Chico and his M.S. in Political Science from the University of Tübingen, Germany. He is presently Coordinator for International Expansion of the ECG.

Footnotes:

1- David RICARDO: "On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation", Batoche Books, Kitchener, 2001, p. 90.

2- Paul BAIROCH (1993): "Economics & World History. Myths and Paradoxes", The University of Chicago Press.

3-Ha-Joon CHANG (2003): „Kicking Away the Ladder. Development Strategy in Historical Perspective", Anthem Press, London/New York.

4- Thomas FRIEDMAN L. (2000): „The Golden Straitjacket", p. 101 - 111 in „The Lexus and the Olive Tree", NY Anchor Books, New York.

5- Dani RODRIK (2012): "The Globalization Paradox", Oxford University Press.

6- John Maynard KEYNES: "National Self-Sufficiency", The Yale Review, Vol. 22, no. 4 (June 1933), p. 755-769.

7- John Maynard KEYNES: "Proposal for an international Clearing Union", April 1943.

December 6, 2017

An Economy for the Common Good: Building a Balance Sheet for Companies' Impact

By Christian Felber, Contributor

Initiator of the Economy for the Common Good

Oct 18, 2016, 08:25 AM EDT

|Updated Dec 6, 2017

This post was published on the now-closed HuffPost Contributor platform. Contributors control their own work and posted freely to our site. If you need to flag this entry as abusive, send us an email.

More than two thousand years after Aristotle, a growing movement is bridging his division between oikonomia - an economy that supports the common good - and chrematistike - making money.

The movement for an "Economy for the Common Good," launched in Austria in 2010, has gained the support of 2,200 companies in 50 countries. Most recently, a committee of the European Union overwhelmingly supported a recommendation to incorporate the Economy for the Common Good framework into the EU and member-state legal systems.

The framework is an attempt to overcome the confusion over whether capital is a means, or the goal. In oikonomia, money served as nothing more than a means to an end: holistic well-being and the comfort and security it brings. Through chrematistike, however, money turned into a goal in and of itself, wrapped up in the ideology of generating profit and growth, much like in capitalism today. Between these two approaches there has always been a wide gap and painfully little room for common ground, since the objectives are so very different.

Advertisement

Full Costs

Measuring economic and business success in terms of financial bottom line alone does not take into account the costs to society incurred in generating profits. For example, costs to the environment to democracy and human dignity -- to name just a few. The systematic pursuit of strictly financial profits fosters the narrow, short-term, bottom-line-focused vision that's crippling our market system, leaving it unable to serve companies, workers or consumers as it should - let alone the planet.

The concept of promoting general welfare is embedded in the constitutions of sovereign nations around the world -- including the constitution of the United States, where it is stated in the preamble. The pursuit of profit and money purely for money's sake is mentioned nowhere. Yet the contradiction persists and the gap it has created keeps widening.

Clearly it's time to reconcile these two systems, and breath a soul back into economics while re-embedding the economy into our cultural value system in a way that elevates social responsibility and the common good over profit.

Advertisement

With this in mind, a dozen companies in Austria launched, in 2010, an initiative called The Economy For The Common Good (ECG). This idea of a complete and coherent, alternative economic model has since grown into a veritable movement geared toward repurposing economic activity so its fundamental objective is to increase the wellbeing of the population at large as well as the integrity of our planet rather than simply maximizing profits. Since then, it has spread to almost 50 countries and gained the support of 2200 companies and 200 local chapters that work with businesses, governments, universities and civil society.

The movement has recently achieved a first major political success at the European Union level: the EU's Economic and Social Committee has approved an opinion paper requesting that the EU move toward incorporating the ECG into the Union's as well as its member-states' legal frameworks. The paper has the backing of 86% of the members of the Committee.

The centerpiece of the ECG model is the adjustment of success-measurement at every level of the economy bearing in mind the constitutional goal of supporting the common good. In the present system, economic success is measured in relation to means (money) and its accumulation. As monetary indicators, Gross Domestic Product, financial profit and return on investment provide a one-sided assessment of economic activity. They don't account for the economy's true purpose: the satisfaction of human needs, quality of life and the fulfillment of fundamental values. In other words, promoting common good.

Early adopters

Three innovations aim to rectify this: the Common Good Product, the Common Good Balance Sheet and the Common Good Exam of investment projects.

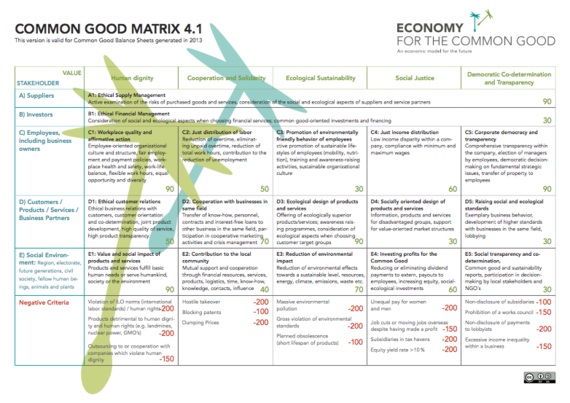

On the company level, the Common Good Balance Sheet measures how firms fulfill key constitutional values that serve the common good. These include human dignity, solidarity, justice, ecological sustainability and democracy. This new balance sheet measures some 20 common good indicators, including:

Advertisement

Sunbeam Multi Zone Air Fryer Oven | Convertible Dual 2x 5.5L Cooking Zone to Single 11.4L Cooking Zo

Sponsored BySunbeam

12

$279.00

Add to cart

Do products and services satisfy human needs?

How humane are working conditions?

How environmentally-friendly production processes?

How ethical are sales and purchasing policies?

How are profits distributed?

Do women and minorities receive equal pay for equal work?

Are employees involved in core, strategic decision making?

To be downloaded here

So far, 400 European businesses have started using the Common Good Balance Sheet and its grading system which awards credits and demerits depending on each company's activities impact the common good. A number of towns in Spain, Italy and Austria have also decided to become Common Good Municipalities with the support of regional parliaments.

The companies and towns rate their activities according to a list of indicators, and the results are examined by external auditors. Each one can reach a maximum of 1000 points. Up until now the average is around 300, which shows that there is still much room for improvement among companies across the board.

If all companies scored 1000 points, we'd have no poverty and unemployment any more, an excellent environment, gender justice, peace, and a well-working democracy.

These companies are using the balance sheet out of sheer interest, without any incentive - although consumers, investors, skilled workers who look for meaningful employment as well as the media public are paying increasing attention to this new business approach. However, ideally an incentive system would be put in place rewarding good results with tax reliefs, lower tariffs, better loan conditions and priority in public procurement among other things.

Tax Treatment

For example, on the trade front, rather than a blanket trade agreement on a country-by-country or regional basis, the U.S. we could require individual companies seeking to sell goods within its borders to present strong Common Good Balance Sheet results. Failing these, tariffs would be applied, increasing progressively as performance declines.

Companies disrespecting international labor standards -- say, through child labor or poor health and safety conditions -- or ravaging the environment would be hard hit. So would those engaged in any form of dumping, from wages to taxes.

Ultimately, ethical products and services would become cheaper for consumers than less ethical ones, and only socially responsible businesses could survive. Non-ethical business would find themselves either forced to change or facing insolvency. The Common Good Balance Sheet would become as important as today's financial balance sheet.

Then, perhaps, chrematistike capitalism would evolve into a different, stronger system benefitting all. And Aristotle could smile down as economic and business practices move closer to the oikonomia he prefererred.

December 6, 2017

Re-Purposing The Economy Can Help Stem The Tide Of Terror

Re-Purposing The Economy Can Help Stem The Tide Of Terror

By Christian Felber, Contributor

Initiator of the Economy for the Common Good

Aug 24, 2016, 05:03 AM EDT

|Updated Dec 6, 2017

This post was published on the now-closed HuffPost Contributor platform. Contributors control their own work and posted freely to our site. If you need to flag this entry as abusive, send us an email.

In the immediate aftermath of World War II the German state of Bavaria wrote a new constitution stating that all economic activity should serve the common good. This was a direct response to the fascism that triggered the war, the Great Depression that gave rise to fascism and the laissez-faire economic and financial system that brought on the Great Depression.

But Bavaria was no pioneer in advocating for the common good: promoting general welfare is one of the bases of the United States constitution, stated in the preamble.

Today, as we contemplate the terror and violence infecting our world from France, Brussels and Bangladesh to Orlando and Dallas, the parallel with the common good cannot be ignored. Over the last three decades, we have collectively failed to make promoting general welfare a priority, choosing instead to support globalized financial capitalism which aims to maximize opportunities for self-interested speculators eyeing profit, bonuses and privileges for large corporations and the global elite who control them -- the same set of elite that's prepared to wage war in order to the secure natural resources.

It's no secret that the winners have become more powerful and the losers have become ever more frustrated and disaffected.

To a certain extent, society can handle inequality and the resulting marginalization. But what about when that threshold is surpassed? As we are now witnessing, those who've been or who feel left behind, those who are left without without opportunities or hope, lash out with aggression and violence.

Thus, today, we are paying the price in fear and bloodshed of having forgotten the lessons embedded in the Second World War's inception.

But it's not too late. The growing outcry against inequality, the vociferous calls for fair trade instead of free trade and human rights instead of corporate rights as we've seen through the Bernie Sanders movement among others suggests that the tides can -- and may well -- change. It won't happen overnight, but with the right level of commitment to re-purposing our global economy through the following initiatives, we can help it take root:

Advertisement

It's Trending Beauty Week with Garnier

Sponsored ByGarnier

34

$8.48

$16.99

50% off Limited time deal

Shop now

A fundamental redefinition of economic success based on an organization's contribution to the common good.

To this end, the adoption of a "Common Good Balance Sheet" for transnational corporations as a condition for accessing global markets. A first attempt at proposing such guidelines was made in the early 2000s by the United Nations, which drafted the "Draft Norms on the Responsibilities of Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises with Regard to Human Rights." This was rejected by business associations and western governments. Now, a better and already widely used instrument - the Common Good Balance Sheet - is available and with the right backing, could become legislation under international law.

The shifting of investment finance priorities from profit goals to common good goals drawing on The Common Good Balance Sheet.

The long-overdue fulfillment of the 0.7 target whereby 0.7% of rich countries respective GNPs would be donated to development assistance through the United Nations.

The payment by rich countries of their outstanding balances due to the United Nations.

A cap on the amount of private wealth that can be held by individuals.

The shifting of priorities from forging international trade deals favoring corporate profit over the welfare of all to taking joint initiatives that support global cooperation, solidarity, sustainability and peace work.

The challenge could not be bigger -- or more urgent. Corporations who view their primary responsibility as serving shareholders are the first who'll need to step up to the plate and consider what entrepreneurial strategies and forms of cooperation will help those who've been excluded from the global economy to find opportunities and their place within it. Governments will need to look at policy instruments such as the Common Good Balance Sheet to support an agenda of human welfare and development rather than a corporate bill of rights.

In sending a clear message through our actions that we're serious about focusing on a common good economy, on local development and sustainability, on fair trade and the strengthening of refugee, poverty reduction and peace programs, we will see the preachers of hatred, revenge and divide would lose their arguments and their targets one by one.

**

Christian Felber is founder of the The Economy For The Common Good based in Austria and the author of 15 books, including, most recently, Change Everything: Creating an Economy For The Common Good (Zed Books-UK, 2015; distributed in the U.S. by the University of Chicago Press).

No comments:

Post a Comment