From Wikipedia,

| Founded | October 6, 2010 |

|---|---|

| Founded at | Wien, Austria |

| Type | Voluntary association |

| Location |

|

Membership | 11,000 |

| Website www.ecogood.org |

Economy for the Common Good (ECG) is a global social movement that advocates an alternative economic model, which is beneficial to people, the planet and future generations.[1] The common good economy puts the common good, cooperation and community in the foreground.

Human dignity, solidarity, ecological sustainability, social justice and democratic participation are also described as values of the common good economy. The movement behind the model started off in Austria, Bavaria and South Tyrol in 2010 and quickly spread to many countries throughout the EU. It now has active groups in Africa, Latin America, North America and Asia.[2] As of 2021, the movement consists of over 11,000 supporters, 180 local chapters[3] and 35 associations.[4]

Christian Felber coined the term "Gemeinwohl-Ökonomie" (Economy for the Common Good) in a best-selling book, published in 2010.[5] According to Felber, it makes much more sense for companies to create a so-called "common good balance sheet" than a financial balance sheet. The common good balance sheet is a value-based measurement tool and reporting method for businesses, individuals, communities, and institutions,[6] which shows the extent to which a company abides by values like human dignity, solidarity and economic sustainability.[7]

More than 2,000 organizations, mainly companies,[8] but also schools, universities, municipalities, and cities, support the concept of the Economy for the Common Good. A few hundred have used the Common Good Balance sheet as a means to do their “non-financial” reporting.[9] These include Sparda-Bank Munich,[10] the Rhomberg Group and Vaude Outdoor.[11] Worldwide nearly 60 municipalities are actively involved in spreading the idea.

The ECG movement sees itself in a historical tradition from Aristotle to Adam Smith[12] and refers to the fundamental values of democratic constitutions.

Overview[edit]

The model has five underlying goals:[13]

The Economy for the Common Good calls for reevaluating economic relations by, for example, putting limits on financial speculation and encouraging companies to produce socially-responsible products.[14]

Common Good Balance Sheet[edit]

The common good balance sheet is an assessment procedure for private individuals, communities, companies and institutions to check the extent to which they serve the common good.[15] Ecological, social and other aspects are assessed.[16][17] The procedure is part of the common good economy and was developed by Christian Felber. In conventional balance sheets, only economic value categories such as profit are taken into account, whereas the common good balance sheet allows reporting on value to society and environment, for example.

Common good balance sheets should be easy for everyone to understand;[18] companies should be able to make their common good performance transparent on a single page.[19][15] In doing so, companies can decide whether to prepare the balance sheet on their own, assess each other in a "peer-group", or appoint an independent auditor.[20][15] This distinguishes the common good balance sheet from conventional sustainability reports, which are prepared by the companies themselves.[16] The balancing process for small companies is relatively cheap (1,000 Euros).[21]

To date, around 250 companies in the German-speaking world prepare their balance sheets according to Gemeinwohl guidelines,[16][22][23][24] in Europe there are 350-400 companies (as of early 2016).[25][26][27] In total, there are 590 German, 631 Austrian, 67 Swiss and 70 South Tyrolean companies that have registered as supporters of Gemeinwohl-Bilanz.[28][29] All peer-group and externally audited Gemeinwohl-Bilanzen are publicly available.[30]

According to proponents of the movement, the success of a company should not be determined by how much profit it makes, but rather by the degree to which it contributes to the common good.[31] Companies receive more points in this balance sheet when, for example, employees are satisfied with their jobs or when the top managers do not receive exorbitantly more than the lowest paid worker.[32]

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Christian Felber: Change Everything: Creating an Economy for the Common Good, ZED Books 2015, ISBN 9781783604722.

- The ‘economy for the common good’, job quality and workers’ well-being in Austria and Germany by Ollé-Espluga L, Muckenhuber J, and Hadler M. The Economic and Labour Relations Review. 2021;32(1):3-21. doi:10.1177/1035304620949949.

- The New Systems Read: Alternatives to a Failed Economy, Edited by James Gustave Speth and Kathleen Courrier, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, New York and London, 2020, ISBN 978-0-367-31339-539-5.

- A corporate balance sheet with a little added love, Chris Bryant, Financial Times, Nov. 19, 2014.

- Microvinyas: ethical vineyards producing wine for the common good, Trevor Baker, The Guardian, Jan. 21, 2014.

- Can we create an 'Economy for the Common Good'?, Bruce Watson, The Guardian, Jan. 6, 2014.

- Economy for the Common Good, Diego Isabel, Article for Network of Wellbeing, May. 08, 2014.

- The Economy for the Common Good, DowneastDem, Daily Kos, Dec. 9, 2013.

- Climate Summit Trap: Capitalism's March toward Global Collapse, Harald Welzer, Spiegel Online, Dec. 9, 2013.

- Christian Felber: Die Gemeinwohl-Ökonomie, Eine demokratische Alternative wächst. Aktualis. u. erw. Neuausg., Zsolnay 2012, ISBN 3-552-06188-6, ISBN 978-3-552-06188-0.

- Christian Felber: Die Gemeinwohl-Ökonomie - Das Wirtschaftsmodell der Zukunft, 2010, ISBN 978-3-552-06137-8.

- Article on Economy for the Common Good from the P2P Foundation

- Die Furche: Die Gemeinwohl-Ökonomie, August 26, 2010

- The Common Good, by Manuel Velasquez, Claire Andre, Thomas Shanks, S.J., and Michael J. Meyer

- Den Menschen soll es gut gehen, by Donato Nicolaidi, Sueddeutsche Zeitung, July 6, 2020

References[edit]

- ^ Bernd Sommer, Klara Stumpf, Ralf Köhne, Josefa Kny, Jasmin Wiefek (2019), "Die zivilgesellschaftliche Bewegung der "Gemeinwohl-Ökonomie" (GWÖ) aus Perspektive der sozialwissenschaftlichen Transformationsforschung und Praktischen Philosophie", Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts- und Unternehmensethik : Zfwu (in German), Baden-Baden: Nomos, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 448–457, doi:10.5771/1439-880X-2019-3-448, ISSN 1439-880X, S2CID 213433319, 2017203-5

- ^ Lindner, Matthias. "Who is ECG". Economy for the common good. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

- ^ "Local Chapters". Economy for the common good. Archived from the original on 2020-07-12. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

- ^ "Economy for the Common Good - Official Website". Archived from the original on 2009-11-21.

- ^ Felber, Christian (2010). Die Gemeinwohl-Ökonomie – Das Wirtschaftsmodell der Zukunft. Deuticke. ISBN 978-3-552-06137-8.

- ^ Niklas S. Mischkowski, Simon Funcke, Michael Kress-Ludwig, Klara H. Stumpf (2018-12-01), "Die Gemeinwohl-Bilanz – Ein Instrument zur Bindung und Gewinnung von Mitarbeitenden und Kund*innen in kleinen und mittleren Unternehmen?", NachhaltigkeitsManagementForum | Sustainability Management Forum (in German), vol. 26, no. 1, pp. 123–131, doi:10.1007/s00550-018-0472-0, ISSN 2522-5995, S2CID 254059236

- ^ Meier, Susanne (Nov 17, 2012). "Menschlichkeit statt Finanzgewinn 16 Tiroler Pionier-Unternehmen erstellen erstmals eine Gemeinwohlbilanz, indem sie ihre Firma in Punkten wie soziale Gerechtigkeit und ökologische Nachhaltigkeit bewerten". Tiroler Tageszeitung.

- ^ "Pionierunternehmen". web.ecogood.org. Archived from the original on 2020-08-12.

- ^ "What is ECG". Economy for the common good. Archived from the original on 2020-07-02. Retrieved 2021-04-26.

- ^ Common Good Report from the Sparda Bank Munich, Germany, 2011

- ^ Spengler, Hanna (November 8, 2012). "Kooperation statt Konkurrenz - Die "Gemeinwohl-Ökonomie"". aktuell.

- ^ "Gemeinwohl in der Geschichte".

- ^ Christian Felber and Gus Hagelberg. "The Economy for the Common Good - A Workable, Transformative Ethics-Based Alternative" (PDF). The Next System Project.

- ^ Koch, Hannes (April 14, 2012). "Der Finanzmissionar - Ein österreichischer Wirtschaftsprediger will den Kapitalismus von innen angreifen – ganz freundlich. Jetzt hat er sich mit einem bayerischen Banker verbündet". die tageszeitung.

- ^ a b c Arbeitsbuch zur Voll-Bilanz, Version 5.0, Stand: 2018

- ^ a b c Öko-Versorger Polarstern zieht eine Gemeinwohlbilanz, von Jonas Gerding, Wirtschafts-Woche, 29. Februar 2016

- ^ 3. Internationale Gemeinwohl-Bilanz-Pressekonferenz, Fona, Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, 24. April 2014

- ^ Profit ohne Maximierung, von Markus Klohr, Stuttgarter Nachrichten, 10. März 2016

- ^ Gemeinwohl-Ökonomie und Energiewende, PV Magazin, 24. Februar 2016

- ^ Wie nachhaltig ist mein Unternehmen?, von Anne Haeming, Spiegel-online, 26. Mai 2016

- ^ Punkten für Gemeinwohl-Bilanz, Merkur.de, 9. Juli 2015

- ^ Ein Banker geht aufs Ganze, enorm, Ausgabe 1/2016

- ^ Gemeinwohl-Bilanz: Darum will eine Freiburger Firma mitmachen, Badische Zeitung, 16. Dezember 2014

- ^ Die Gemeinwohl-Bilanz, Unternehmen sollen Nutzen stiften, nicht nur Rendite, Forum Nachhaltig Wirtschaften, 1. Januar 2015

- ^ Das aktuelle Wirtschaftssystem produziert eine Endlosreihe von Kollateralschäden, Die Farbe des Geldes, online-Magazin der Triodos Bank, 3. Juni 2016

- ^ Gemeinwohl-Orientierung bringt Unternehmen langfristig Vorteile, Schwäbische.de, 22. April 2016

- ^ Ökonomen wollen Ex-Attac-Aktivist Felber aus Lehrbuch streichen, von Andreas Sator, Der Standard, 8. April 2016

- ^ UnterstützerInnen der Gemeinwohlökonomie

- ^ Die Saubermänner, von Elena Witzeck, Süddeutsche Zeitung, 10. März 2016

- ^ GWOe-Berichte, Gemeinwohl-Ökonomie

- ^ Johannes Pennekamp: Die Bessermacher. In: der Freitag Newspaper. September 26, 2011

- ^ Guido Mingels: Die Achse der Guten. In: Der Spiegel. October 10, 2011

External links[edit]

Economics for the Common Good :

Economics for the Common Good Hardcover – Illustrated, 14 November 2017

by Jean Tirole (Author), Steven Rendall (Translator)

4.4 out of 5 stars 224 ratings

Kindle $21.72

Hardcover $42.34

From Nobel Prize-winning economist Jean Tirole, a bold new agenda for the role of economics in society When Jean Tirole won the 2014 Nobel Prize in Economics, he suddenly found himself being stopped in the street by complete strangers and asked to comment on issues of the day, no matter how distant from his own areas of research.

576 pages

Product description

Review

Endorsements:

From the Back Cover

"I predict that Jean Tirole's Economics for the Common Good will join Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century as the two most widely read and important books by economists yet to be published in this century. With Tirole's terrific, wisdom-filled book, the world will be a better place."--Glenn Loury, Brown University

"Jean Tirole is that rare exception, a Nobel laureate who believes he has a responsibility to talk clearly about the concerns of noneconomists. This exceptional book shows the value of careful economic thinking on issues ranging from unemployment to global warming. It should be required reading for policymakers, but also for anybody else who wants to understand today's economy."--Olivier Blanchard, former Chief Economist of the International Monetary Fund

"Jean Tirole puts at center stage the essential contribution of economics, and economists, to our shared hopes and aspirations for the societies we live in. This is an essential book with a hopeful message for anyone concerned about the key economic challenges we all face today."--Diane Coyle, author of GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History

Product details

Publisher : Princeton University Press; 1st edition (14 November 2017)

Language : English

Hardcover : 576 pages

4.4 out of 5 stars 224 ratings

Top reviews

Jeffrey Sayer

4.0 out of 5 stars Excellent overview of the role of economicsReviewed in Australia 🇦🇺 on 28 September 2018

Verified Purchase

I greatly enjoyed this book, it provides a clear and relevant discussion of many of the tricky economic conundrums that confront the world. The book left me concerned that we are allowing our countries and the world to be run by politicians who do not understand these fundamental economic realities

Hande Z

5.0 out of 5 stars Hard times indeed...Reviewed in the United Kingdom 🇬🇧 on 30 January 2020

Verified Purchase

There is a fundamental problem with economists – they are seldom right. Could the problem be economics itself? This is an underlying theme in this book even as the authors strived to discover why economists do not agree with each other, and why the public often do not agree with the government and the economists who advised them.

The authors discuss whether free trade is the solution for poor economic growth, or is free trade the problem? They study countries (such as India) that have gone through different approaches and arrived at uncertain conclusions. After opening up to trade – in return for IMF money – it took India more than a decade after 1991 to see economic growth. They discuss the economic benefits of tariffs versus free trade. The conclusions are far from clear, because trade and growth are a complex mix, but it seems that tariffs often backfire.

Economic growth id not entirely dependent on trade, and even in trade, one factor stands out in contrast to capital – labour. Once the authors launch into the supply of labour, we see the problems of immigration and racism. The authors point out that the traditional bias against immigrant workers is mistaken. People do not move just because the pay is better elsewhere. In fact, we are blinded into not seeing that people generally do not like to move, and there are many strong reasons for that. There is the issue of connection. People are more likely to move if they have connections in their intended destination. Then there are family ties back home, in contrast to the poor living conditions elsewhere, and so on. The authors also point out that anti-immigrant sentiments have existed from time immemorial, only the subject changes. First people were against Jewish immigrants, then Italian immigrants, then African immigrants, and now, it is Muslim ones. Eventually, the authors say, the immigrants get assimilated, and the nation’s attention (or prejudice) turn to others.

The authors examine and analyse the factors that lead to growth and those that do not. The question whether using GDP is the accurate way to measure growth. In the history of modern times, there has only been one growth spurt, and that ended on 16 October 1973 with the Arab oil embargo – a spurt never to return, say the authors.

The authors presented a detailed and persuasive argument that taxation is beneficial and useful in lowering the inequality gap. They explain that when people get poor, they tend to blame the wrong factors, for example, immigrants for taking away their jobs. Lowering the income inequality is thus a important priority. Unfortunately, politicians do not have the will to impose or increase taxes. The authors further explain that taxing the rich helps but not enough. There should be a wealth tax on the assets of the rich. They present powerful arguments as to why that is so.

This is a remarkable book that covers a wide range of economic topics with an aim of making the dots connect, and disabusing us of seeing magic dots that don’t connect. It is a book worth reading even if one is sceptical about some of its claims – after all, the Messiah of Economics has yet to come.

Read less

Report

erkki

5.0 out of 5 stars Perhaps the most important book on Economics during last year.Reviewed in the United Kingdom 🇬🇧 on 3 February 2018

Verified Purchase

Jean Tirole's Economics for the Common Good is one of the most important books of the year, if not the most important. It is valuable for policy-makers, since it proves that economics has produced many tools that can be used in finding the best possible solutions.

The book sends an important message to economists that they can bring their important to the socieatal debate by sharing the results of the research. Economists may have also their personal views on values, but the objectivws based on values of society must be left to the democratic process.

The book is important for any citizen who is interested on what economics can bring to the solutions of today`s problems in many areas.

2 people found this helpfulReport

Amazon Customer

5.0 out of 5 stars Very good book which achieves what it set out to doReviewed in the United Kingdom 🇬🇧 on 29 November 2017

Verified Purchase

A voice of and for reason. Very good book which achieves what it set out to do. Particularly good on digitization, labour markets innovation and sector regulation.

2 people found this helpfulReport

John

1.0 out of 5 stars Boring and turgidReviewed in the United Kingdom 🇬🇧 on 15 October 2019

Verified Purchase

He won a Nobel prize and is surely a great academic, but he cannot write for a mainstream audience

Report

Amazon Customer

4.0 out of 5 stars AcademicReviewed in the United Kingdom 🇬🇧 on 27 May 2018

Verified Purchase

Best for economics students.

One person found this helpfulReport

See all reviews

====

Sample

Economics for the Common Good

By: Jean Tirole, Steven Rendell - translator

Narrated by: Jonathan Davis

Length: 18 hrs and 54 mins

3.7 out of 5 stars3.7 (3 ratings)

1 CREDIT

Non-member price: $41.73

Member price: $14.95 or 1 Credit

Buy Now with 1 Credit

Buy Now for $14.95

Add to basket

More options

Share

Publisher's Summary

From Nobel Prize-winning economist Jean Tirole, a bold new agenda for the role of economics in society.

When Jean Tirole won the 2014 Nobel Prize in Economics, he suddenly found himself being stopped in the street by complete strangers and asked to comment on issues of the day, no matter how distant from his own areas of research. His transformation from academic economist to public intellectual prompted him to reflect further on the role economists and their discipline play in society. The result is Economics for the Common Good, a passionate manifesto for a world in which economics, far from being a "dismal science," is a positive force for the common good.

Economists are rewarded for writing technical papers in scholarly journals, not joining in public debates. But Tirole says we urgently need economists to engage with the many challenges facing society, helping to identify our key objectives and the tools needed to meet them. To show how economics can help us realize the common good, Tirole shares his insights on a broad array of questions affecting our everyday lives and the future of our society, including global warming, unemployment, the post-2008 global financial order, the euro crisis, the digital revolution, innovation, and the proper balance between the free market and regulation. Providing a rich account of how economics can benefit everyone, Economics for the Common Good sets a new agenda for the role of economics in society.

PLEASE NOTE: When you purchase this title, the accompanying reference material will be available in your Library section along with the audio.

©2017 Princeton University Press (P)2018 Audible, Inc.

Product Details

Unabridged Audiobook

Release date: 15-05-2018

Language: English

Publisher: Audible Studios

Learn more

TheoryUnited States

More from the same

NarratorGenghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World

Sex at Dawn

Snow Crash

What listeners say about Economics for the Common GoodAverage Customer Ratings

Overall 3.5 out of 5 stars3.7 out of 5.0

5 Stars

0

4 Stars

2

3 Stars

1

2 Stars

0

1 Stars

0

Performance 4 out of 5 stars4.0 out of 5.0

5 Stars

1

4 Stars

1

3 Stars

1

2 Stars

0

1 Stars

0

Story 4 out of 5 stars4.0 out of 5.0

5 Stars

1

4 Stars

1

3 Stars

1

2 Stars

0

1 Stars

0

Reviews - Please select the tabs below to change the source of reviews.

Audible.com.au reviews

Audible.com reviews

Amazon Reviews

Sort by:

Filter by:

Overall

4 out of 5 stars

Performance

3 out of 5 stars

Story

4 out of 5 stars

Zach Sullivan

06-08-2018

A Great Overview of the Challenges of Modern Econ

Tirole provides a comprehensive yet succinct take on a wide array of the many issues facing twenty-first century economics. Far from resorting to a tribalistic defence of his fellow economists, Tirole acknowledges many of the shortcomings of his field, yet also takes great care to debunk some of the more fallacious criticisms raised by non-economists. From the outset, much consideration is given to the disruptive impact of cognitive biases, imperfect information, and other real world constraints faced by those contemplating economic problems.

Importantly, Tirole identifies the paramount importance of nuance when discussing economic policy decisions, and approaches the critique of his own discipline from a highly empirical and self-critical standpoint. Ultimately, his overview of economics is sensible and well-grounded, non-dogmatic, -and most importantly-, careful to identify areas in which economics can be used to make the world a better place.

On top of this, the narrative performance by Jonathan Davis is decent enough, however, I would recommend also following along closely with the accompanying PDF if you are to get the most out of this book.

If you are looking for one book providing a well-informed critique of modern economics that is accessible to both professional economists and laypeople alike, then this is the title for you.

2 people found this helpful

Overall

1 out of 5 stars

Performance

1 out of 5 stars

Story

1 out of 5 stars

Puppy Luv

05-02-2022

- Encourages lack of responsibility for actions

- This book encouraged lack of responsibility for actions and focused on a socialist/communist approach to economics.

- It is difficult to listen to while driving due to the content. if someone really wanted to learn about economics, try anything else.

- this book promotes laziness and lack of accountability of actions. it's read in a monotone voice so could easily put someone to sleep.

Overall

5 out of 5 stars

Performance

5 out of 5 stars

Story

5 out of 5 stars

DNM

13-12-2020

Must read for all responsible citizens

This book answered many issu

=

====

Economics for the Common Good Summary and Review

by Jean Tirole

Has Economics for the Common Good by Jean Tirole been sitting on your reading list? Pick up the key ideas in the book with this quick summary.

It’s sometimes called the “dismal science,” but the weird and wonderful world of economics is anything but drab. As a clear-eyed observer of the world, Nobel Prize-winning French economist Jean Tirole can draw upon decades of economic expertise to illuminate common features of the world in a surprising, and often downright counterintuitive, light.

Between demonstrating why an anti-poaching NGO should sell confiscated ivory tusks rather than destroy them and explaining the debt crisis in southern Europe, Tirole takes a look at the big topics that shape our present and will determine our future.

Why do we need finance markets even after speculators demonstrated their recklessness in the 2008 financial crash? What stops us from tackling the looming threat of drastic climate change, despite the repeated warnings of scientists? And how can the state and free markets best be brought together to guarantee growth, innovation and the common good? These are just some of the burning questions this book summary will take on.

In this summary of Economics for the Common Good by Jean Tirole,You’ll also find outwhat makes the tragedy of the commons so tragic;

what economists can learn from their colleagues in the humanities; and

how the 2008 financial crisis started with dodgy mortgages.

Economics for the Common Good Key Idea #1: Our understanding of how the economy works is shaped by confirmation biases.

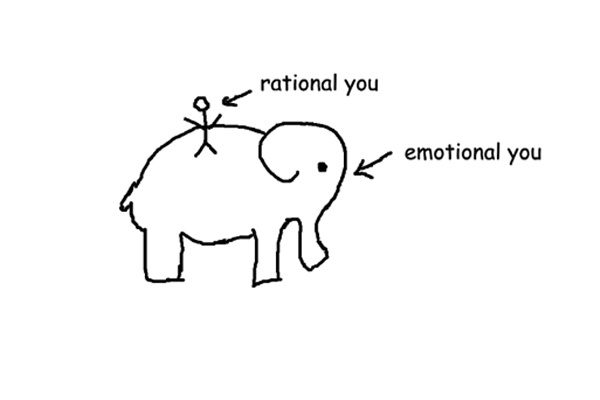

The way we see the world is shaped by our beliefs. We emphasize facts that confirm ideas we already hold, which is why we read newspapers that echo our own political views and seek out like-minded friends.

Economics is no different; our preexisting beliefs mold our attitudes toward the facts.

This means we often don’t make the wisest economic decisions. Instead of looking at the evidence and making decisions accordingly, we look for simple rules that we can apply to every new situation.

This approach can lead us astray because economics can be deeply counterintuitive.

Imagine an environmental NGO that campaigns against poaching. It’s just managed to intercept a consignment of ivory tusks being shipped by a group of poachers who kill endangered elephants. What should it do with the confiscated ivory?

Moral intuition tells us that the trade in illegal ivory is reprehensible, which means we should destroy it, right?

No! Economic reasoning suggests that the best option would be to do what the poachers were attempting to and sell the ivory.

But, you may ask, wouldn’t that just put the NGO in the same shoes as the poachers? Not quite. Selling the ivory would raise the needed funds that would allow the organization to continue its work in the future. Not only that, releasing the ivory onto the market would depress the value of elephant tusks by making them less scarce thus reducing the incentive of poachers to kill other elephants.

As you can see, taking a long-term perspective of the kind offered by economics changes the moral calculus involved in all sorts of decisions.

This doesn’t mean that economics is purely about cold rationality. Think of a market. At its simplest, it’s just a mechanism to allocate scarce resources; buyers and sellers meet in the marketplace to consensually exchange goods and services.

But markets aren’t the infallible mechanisms they’re sometimes perceived to be. Not every good can be bought and sold freely, and some things, like ivory, need to be more strictly regulated than others.

Imagine, for example, a market in which babies could be traded for cash by parents (the sellers) and adopters (the buyers). It’s easy enough to envisage both parties reaching a mutually beneficial agreement.

But here, economists would raise an objection. From their point of view, this exchange fails because it neglects the interests of a third party, namely the baby. This kind of market failure is the result of what economists call an externality – the cost of an exchange borne by a third party who can’t consent to the exchange.

And that’s where regulation comes in. It’s an attempt to safeguard the interests of all parties to an exchange, whether they’re those of babies, elephants or the environment.

Economics for the Common Good Key Idea #2: Economists try to make the world a better place by providing insights for policymakers.

What exactly is it that economists do? Lots of things in fact, but two roles stand out.

Because they’re often ensconced in the ivory towers of academia, one of economists’ most important tasks is contributing to our knowledge of the world. But they also have another, less theoretical, role: economists try to make the world a better place by providing insights that policymakers can act upon.

That means economists often play an important part in public debates.

Take climate change, for example. Scientists tell us that the best way to prevent catastrophic global warming is to stay within our allocated annual “carbon budget” and cut the amount of greenhouse gases we emit each year.

Because knowing about budgets is pretty much in economists’ job description, they’re ideally placed to help us figure out the most efficient – and least costly – way of allocating our carbon budget.

So how do economists go about tackling problems like this? They rely on models to analyze actors’ behavior. Two theories are particularly suited to this purpose.

The first is game theory. This is essentially a way of modelling the behavior and strategies of self-interested actors who are also interdependent and affected by each other’s actions.

A famous example is the “prisoner’s dilemma,” a thought experiment that looks at how two prisoners will behave without knowing what the other is doing – will they betray each other in search of a more lenient sentence or keep quiet?

Game theory asks two questions about this kind of situation: First, what’s the best decision for the individual? And second, what’s the best decision for multiple parties collectively?

Another helpful tool is information theory, which centers on the way individuals make use of private information.

To get an idea of how this works, imagine a tenant farmer and a landlord. The owner of the land has private information – something that only he knows – about the fertility of a parcel of land that he wants to lease to a farmer. When the time comes to draw up the contract with his new tenant, he might well propose a profit-sharing model rather than renting the land for a fixed sum. After all, he knows how fertile the land is and is confident that it will generate large returns.

Analyzing private information lets economists make informed predictions about individual behavior. And knowing what people are likely to do in certain situations is a great basis for making policy recommendations.

Economics for the Common Good Key Idea #3: Economics has a lot to learn from the social sciences and humanities.

Economic theory begins with a fairy tale. Once upon a time, it says, there was the homo economicus. This fabled character from economics 101 textbooks is the self-interested and rationally calculating decision maker. But as anyone who’s ever felt the lure of unhealthy junk food knows all too well, humans just aren’t perfectly rational creatures.

What else drives us then? One place economists can look for answers is in the social and human sciences.

From philosophy to law, history to psychology or sociology to political science, all these disciplines have one thing in common: they’re all concerned with what makes people, groups and organizations tick. Their attempts to get at the heart of the human condition have introduced us to a whole raft of characters to complement homo economicus.

Take psychology’s homo psychologicus. He’s far from rational, and psychologists are largely interested in exploring the hidden drives that lead him to make decisions that sacrifice his long-term interests for short-term pleasures. Why, for example, does he spend all his money today rather than putting a portion of it away for a rainy day or his retirement?

Psychology is also useful if you want to understand behavior that isn’t self-interested. What makes us empathetic and capable of giving without expecting anything in return?

Sociology adds another character to our expanding cast – homo socialis. What can an economist learn from this figure? Well, economies are social systems that depend on values like trust. Because we don’t always have access to all the information we need to make informed decisions, we often buy things because we trust the seller or a recommendation from someone else.

But it’s not just trust that underpins economies. If you want to understand why someone obeys the rules and pays their taxes (or doesn’t), it’s useful to get a handle on another character, homo juridicus, since behavior is shaped both by legal and social norms.

Economics for the Common Good Key Idea #4: Neither the state nor the market is perfect and they both need each other to function properly.

The market and the state are frequently depicted as belonging to entirely separate spheres. But contrary to what is often said about them, they don’t compete with each other; in fact, each needs the other to work properly.

That’s because they do different things. Take markets. Without them, there’d be little competition or innovation. Yet without the state and the rule of law, markets would descend into anarchy. After all, businesses need protecting and contracts have to be enforced for a market to work at all. And, as we’ve seen, it’s the state that provides a regulatory oversight that protects the common good when markets fail.

But it’s not just markets that occasionally fail – states can too.

Consider politicians. What they want above all else is to be elected or reelected, which is logical enough since they’d be unable to do anything if they didn’t have power. But that search for approval at the ballot box can also distort their decision making.

This is a common theme on the campaign trail, when politicians exploit voters prejudices or ignorance rather than try to change people’s minds.

A more dangerous practice is pandering to special interest groups. Promising groups of voters what they want is a great way of getting them to turn out come election day, but it’s not necessarily a brilliant way of crafting economic policy. Promises are easy to make and hard to deliver on.

That’s especially true in the case of spending commitments, because their true cost can be difficult to calculate. Investing in creaky public transport infrastructure might sound like a no-brainer during a stump speech, but what if the state needs to borrow money to fix the transit system? The final bill can easily exceed the rough-and-ready arithmetic of politicians casting around for votes!

Businesses face a similar quandary when it comes to decision making. Who gets to make the decisions and why?

Every business has multiple stakeholders – groups affected by how a business operates. Balancing the interests of different stakeholders can be a tricky matter.

Take two stakeholders found in virtually every business: investors and employees. If the former dictate policy, they might be tempted to ignore the interests of the company’s workers and end up slashing jobs in search of bigger profit margins. Conversely, if employees get the upper hand, they might also let short-term gains get in the way of long-term strategies and simply raise their own wages while leaving too little for reinvestments.

Therefore, both the state and businesses can fail when they don’t make informed choices that take into account the interests of all stakeholders.

Economics for the Common Good Key Idea #5: Climate change looks like an intractable problem, but economists have already devised potential solutions.

From rising sea levels to extreme weather events and more frequent droughts, the effects of global climate change are likely to be catastrophic unless we take action soon.

But policies like reducing greenhouse gas emissions that would help to counteract global warming are extremely difficult to implement – and economists can help us understand why.

Failure to take action on climate change is an example of what economists call the tragedy of the commons, which essentially refers to a conflict of interest between individuals and the common good.

Imagine what would happen if greenhouse gas emissions were reduced globally. Everyone would benefit, right? The problem is that this could only be brought about by individual countries implementing the right policies. But because the switch to cleaner energy sources and lowering emissions is costly, there’s a strong disincentive to put those policies in place at the national level.

That’s compounded by the fact that each country represents only a small fraction of the total population of the earth. At the national level, the benefits of environmentally friendly policies would be relatively small.

So there’s a strong incentive to free ride. Countries that fail to change their individual behavior and continue polluting the atmosphere can still stand to benefit from difficult changes made by others.

The tragedy of the commons is the result of widespread free riding. Everyone needs to adopt policies that counteract the effects of climate change, but no one has an incentive to implement them individually.

It’s because of this situation that voluntary measures to fight climate change have failed.

The 1997 Kyoto Protocol is a good example. Although a large number of countries signed up to an agreement to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions, there was plenty of free riding, notably by countries like the United States, which never ratified the protocol.

Economists have come up with two policy proposals that they think might be able to cut through this Gordian knot.

The first is a global carbon tax. Polluters would be charged a fixed price per ton of emitted carbon dioxide, wherever they were in the world, by the responsible state authority.

The second option proposed by economists is a system of tradable emission permits. This would require setting a global ceiling for the amount of greenhouse gases that can be emitted each year. Governments would then issue permits to emit a certain tonnage of carbon dioxide, which could be freely traded by companies.

Economics for the Common Good Key Idea #6: Southern European countries have problems with the labor market, competitiveness and debt.

Millions of Europeans are worried about their economic future – and it’s no wonder. The continent’s economy faces a number of serious challenges, especially in southern European countries.

Unemployment in countries like Greece, Spain and France is sky-high when compared to the countries of northern Europe, the United States and Canada. It’s especially bad for two distinct age groups: young people aged between 15 and 24 at the start of their careers, and older people between 55 and 65 at the end of their careers. Worse still, many of these people are experiencing long-term unemployment.

The labor market itself is a daunting prospect for job-seekers. Many jobs are short-term, unfulfilling and insecure, while better-paid jobs require extensive training, the cost of which is a burden mostly borne by taxpayers.

Southern Europe has other problems, too.

The introduction of the euro as a common currency in 1999 was designed to increase European integration and hasten economic development, but it has come at a high cost.

Since 1999, many countries in southern Europe have seen salaries rise faster than productivity. That has made their economies much less competitive than they need to be in today’s global economy. Before the euro, they could devalue their individual currencies to boost competitiveness, but that option has been off the table since the introduction of a common currency controlled by a European central bank.

Both private and public debt has been piling up over the same period. High debt means high interest rates, especially once banks start to worry about whether countries are capable of servicing their debt at all. That has added to the pressure on southern European treasuries.

So what’s to be done? One ambitious proposal is to move toward a federal European state in which risks are shared equally by all member countries.

Economics for the Common Good Key Idea #7: Financial speculation has its uses – but it can also be dangerous.

Few topics in economics are as fiercely and emotionally contested as finance. That’s partly a legacy of the financial crisis of 2008, and the resulting widespread view of bankers as reckless speculators who crashed the global economy.

But finance is one of those things we just can’t do without – if we could, we’d have already gotten rid of it and spared ourselves the expensive and tricky public bailouts of recent years!

So what is finance?

Basically, it’s a service for borrowers. Consider a mortgage; the bank provides borrowers with credit to acquire something they couldn’t otherwise.

It’s not just households that borrow money though – businesses and governments also need ready access to credit to keep the show on the road. It’s hard to imagine an economy functioning without borrowing and lending.

The finance sector also provides insurance against risk. Without that safety net, borrowers could easily end up in trouble.

A good example of this is the aircraft manufacturer Airbus. Most of the company’s earnings are in dollars, while its expenses are paid in euros. That means it’s vulnerable to sudden fluctuations in the dollar-euro exchange rate – if the dollar dropped sharply, the company would have trouble paying its bills. Insurance against fluctuations of this nature is a vital safety mechanism for Airbus.

But as the financial crisis demonstrated, financial speculation can also destabilize the economy. This happens when otherwise useful financial products turn toxic, and a major cause of that is securitization, the financial practice of pooling different kinds of debt and selling it to a third party.

Let’s return to our example of a mortgage on a house. Once the bank has lent you the money, it can either decide to keep the loan on its books and collect the repayments over the next 30 or 40 years, or it can sell the loan to another bank.

There’s nothing wrong with trading in loans in principle – in fact, it’s essential if a bank wants to diversify its portfolio or reinvest its assets. So what’s the catch? Well, if a bank knows it can always flip a mortgage, and get someone else to bear the risks, it’s likely that it’ll become less scrupulous in deciding who’s eligible for a loan.

That’s precisely what happened in 2008. Once people started to notice that a huge number of mortgages had been given to people who couldn’t repay the debt, the whole financial system collapsed like a house of cards. People realized that they were holding assets that weren’t worth the paper they were written on and scrambled to get rid of them, bankrupting many banks in the process.

Economics for the Common Good Key Idea #8: The state is at the heart of economic life, but it’s the market that drives innovation.

We’ve already seen how the state and the market are like the yin and yang of economic life, two interdependent and complementary forces in a larger system. In this book summary, we’ll take a closer look at their relationship.

Paradoxical as it may seem, the state is the at the heart of economic life in every market economy, because it plays three distinctive and important roles within the market.

The first role is one of public procurement. Here, the state becomes a buyer of goods and services for everything from the construction of public buildings, roads and railways to the running of hospitals. This has the beneficial knock-on effect of boosting competition among suppliers.

But the state isn’t only part of the market – it’s also above the market. As a legislative and executive power, it sets the parameters of the market economy by issuing permits and licenses for things like taxi firms, supermarkets and even airline landing rights.

In that role, the state is also a referee of markets. The state is an observer of the play of economic forces, intervening to make sure the rules of the game are upheld and dominant players don’t abuse their power.

So what’s the market’s role then? Open competition in free markets provides several goods that the state on its own can’t.

Take affordability. Monopolies can charge whatever they want for their services because customers can’t go anywhere else. Unsurprisingly, prices are often sky high. Competition means that suppliers have to convince customers to buy their services rather than someone else’s, and lowering their prices is often the most convincing argument of all!

But if you’re a supplier and you want to lower your prices, you’ll also have to find a way to lower your costs. Innovation and efficiency are the side effects of suppliers’ bid to offer competitive prices.

Economics for the Common Good Key Idea #9: Digitalization brings new opportunities and poses new problems.

We’re already living in the digital economy. We shop and bank online, catch up on news and gossip on our smartphones and stay in touch with friends on Facebook.

What the platforms of the new digital economy all have in common is that they’re examples of two-sided markets, markets in which buyers and sellers interact via an intermediary.

Globalization has made the world a smaller place, which means that buyers and sellers from every corner of the earth can exchange goods and services. But as the world has gotten smaller, the global economy has gotten a lot bigger. So how do we decide who to do business with?

Two-sided markets like Amazon make this a lot easier. By providing a digital marketplace, they bring buyers and sellers together wherever they are. But unlike traditional marketplaces, these platforms also act as regulators to ensure that transactions are fair and smooth. In some cases, they even regulate prices – think of Apple’s iTunes, which limits the charge for downloads to $0.99 per song.

But there’s a catch. Digital platforms only work when we trust them not to misuse our personal data.

How can you tell which websites are safe? The answer, troublingly, is that you often can’t. Even large companies have been subject to massive credit card theft in recent years. Forty million customers of Target had their details hacked in 2013, while another 56 million Home Depot customers had theirs stolen the following year and 80 million customers of the health insurance company Anthem had theirs ripped off in 2015.

Add to the mix the often dubious terms of use that many websites make users sign and there’s plenty of cause for concern.

So how can trust be reestablished?

One solution is legislation that protects users against one-sided clauses. We don’t need to look far to see what that might look like in practice, since we already have laws of this kind in the offline world.

Think of a parking lot. If you leave your car there, you accept the property owner’s terms of use. But these terms are strictly limited – they can’t include a clause that says it’s fine for the parking lot owner to take off in your car!

Economics for the Common Good Key Idea #10: Intellectual property rights are a necessary evil in the struggle for greater innovation.

Innovation is the motor that keeps the economy humming and the wheels of economic growth spinning.

But safeguarding innovation requires intellectual property rights.

That might seem like a paradox. Surely it’d be better if innovations were free for all to use and improve upon, right?

Actually, no. The problem is one we’ve encountered before: free-riding. If every innovation were publically available for all to make use of, there would be little incentive for anyone to devote resources to the research and development that underpins all innovation.

That’s why it’s important to protect the income of innovators. By guaranteeing that they’ll profit from their work, tomorrow’s innovators are given an incentive to continue their often difficult and time-consuming work today.

That’s where intellectual property rights come in.

When the state enforces intellectual property rights, it’s effectively granting the creator of an innovation an exclusive license to market and profit from a given product. So, intellectual property rights and innovation go hand in hand.

But this isn’t the only way of boosting innovation; various governments have experimented with alternative models.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, for example, both Britain and France granted prizes to innovators in public competitions. Once the winner had collected his award, the innovation was made accessible to everyone.

While this was a great incentive for innovators to compete amongst themselves, there was also a downside. Innovation is usually unpredictable – no one knows what tomorrow’s technology will look like.

But if you want to give someone a prize, you have to know what criteria you’ll be using to judge his submission; this condition, in turn, narrows the field of innovation.

Companies have also experimented with novel approaches. One idea is patent pools, an agreement among competing firms in the same industry to jointly control patents that they can all use. That is known as coopetition, a portmanteau of the words “cooperation” and “competition,” and has been used to try to lower the price of innovations.

In Review: Economics for the Common Good Book Summary

The key message in this book:

The science of economics is, like the world it attempts to describe, complex. There are rarely clear-cut rules that can be applied to all situations; instead, there are trade-offs between different and equally valuable goods. Failure is often a result of not striking the right balance, whether it’s in the sphere of the state or markets. Getting it right requires an understanding of economics, a discipline that can help us achieve the common good when it comes to the most urgent issues of the day, like climate change and the transition to a digital economy.

If you liked this book summary, also check out:

Purpose

Work ethic

Vulnerability

Happiness

Overcoming anxiety

Effective communication

Anxiety mouse

Habits

Depression

LifeClub © 2019

No comments:

Post a Comment